Wetland wildernesses are all too often lost to the march of development — industrial infrastructure, the encroachment of the city, clearing for agriculture — under the promise of jobs, prosperity and a better life. But, in many cases, what is gained can never replace what was lost, and the benefits are overshadowed by the consequences.

Threats such as saltwater intrusion into crop fields give Youssoupha an even greater incentive to protect the mangroves of the Saloum.

One young wetland ambassador looking for a different way is Youssoupha Sane, a teacher at Mbam village primary school, Senegal — a sleepy village in the Fatick district, upstream from the Saloum Delta.

Just 180 kilometers south-east of Dakar, the Delta is a biodiversity hotspot and UNESCO world heritage site covering some 180,000 hectares of wetlands, lakes, lagoons and marshes, sandy coasts and dunes, terrestrial savannah areas and dry, open forest. It’s home to 400 species, is a source of millions of livelihoods and plays a vital role in flood control and regulating the distribution of rainwater for local people and wildlife.

However, these wetlands have been under pressure on a number of different fronts over the last decade. The discovery of oil in the Sangomar Deep block, off the Senegalese coast close to the National Park of the Saloum Delta, has been a cause for concern. Many, including Youssoupha, are worried about the risks to the Delta.

Many, including Youssoupha, are worried about the risks to the delta.

At the same time, due to drought, climate change and the uncontrolled logging of mangrove forests, the ground’s salinity has shot up – threatening the livelihoods of thousands of people living there, with saltwater intrusion into rice fields and pastoral areas. It’s even more reason to protect the mangroves since they help stop the advancement of salinisation in the crop fields, Youssoupha says.

A local oil spill in 2014, with severe consequences for the community, livelihoods and wildlife, convinced Youssoupha that the wetlands must be safeguarded. Seeing the connections between threats and disastrous outcomes for people and nature, he made it his mission to raise awareness across generations and help foster sustainable development in his community.

Youssoupha has since been teaching at Mbam school alongside 12 other teachers, giving the 420 students a broad education, as well as delving into environmental issues such as waste management and biodiversity. The school forest, introduced a number of years ago, offers habitat for birds, insects and other animals, which students can study first-hand.

Students at the Mbam school have a ‘school forest’ where they can study birds, insects and other animals first-hand.

But, for two years now, school is regularly interrupted, due to the salinisation of the water systems. The lack of freshwater supply has led to the death of many banana plants and forced the shutdown of the school garden. A more systemic approach is needed, and that involves helping local communities make the connection between human actions, disasters and the ways that maintaining the ecosystem can help prevent these disasters.

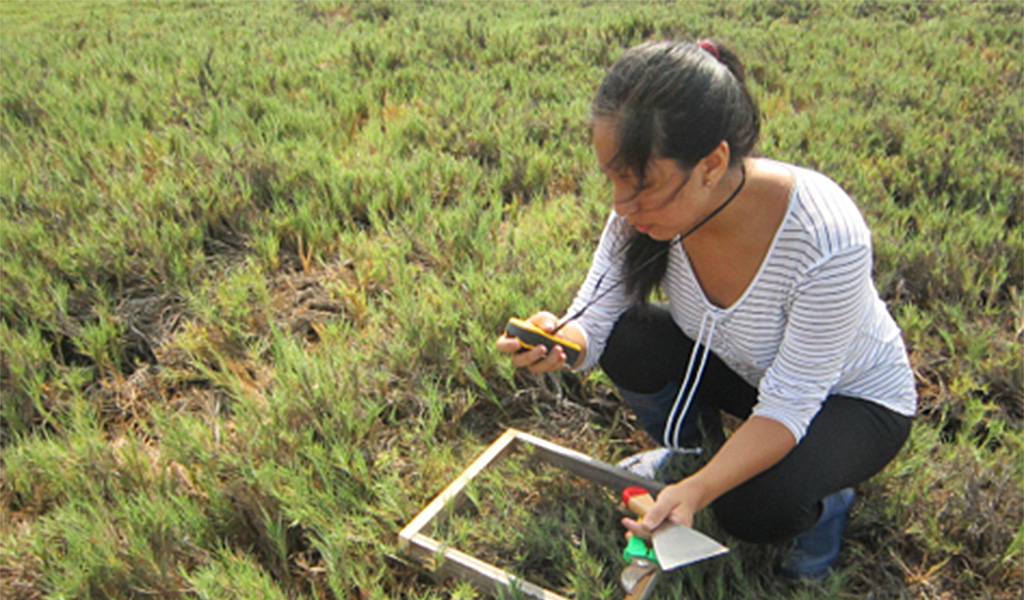

With this in mind, the Mbam 2 Environment Club, coordinated by Youssoupha and which brings together 30 students every year to explore the mangroves, spot wildlife and count waterbirds. By putting their knowledge into action the children learn the complex co-dependencies between the ecosystem and their communities.

“It’s vital to prepare the children for a climate that might threaten their way of life.”

It’s vital to prepare the children for a climate that might threaten their way of life and equip them with the knowledge and actions to protect their environment, says Youssoupha. Ideally, everyone would have access to their own green energy and know how to mitigate the effects of natural and anthropogenic environmental change.

Youssoupha hopes their enthusiasm will help raise awareness among their parents on the importance of the environment, contributing to an increasing focus on sustainability in their region. “They’re awakening the environmentalist fibre,” he says.