Wetlands adjacent to cities are often used as wasteland despite being important carbon stores. The Pantanos de Villa Wildlife Refuge in Peru is such a place.

Los Pantanos de Villa, a coastal marine wetland, was designated as a wildlife refuge, a natural protected area and Ramsar Site in 1997, but being so near to a fast growing urban population, this ‘special interest’ site has become a dump.

Trucks have even been known to dump construction waste there, compacting the soil, reducing flora growth and draining the flooded areas. Soil saturated with water allows the accumulation of carbon because it prevents oxidisation of the soil. In other words, when dry, the soil literally evaporates into thin air. It then loses its ability to store carbon and becomes a source of emissions.

Pantanos de Villa Wildlife Refuge in Peru

“During the day I could observe the birds and on the way home I saw the moon reflecting in the lagoon.”

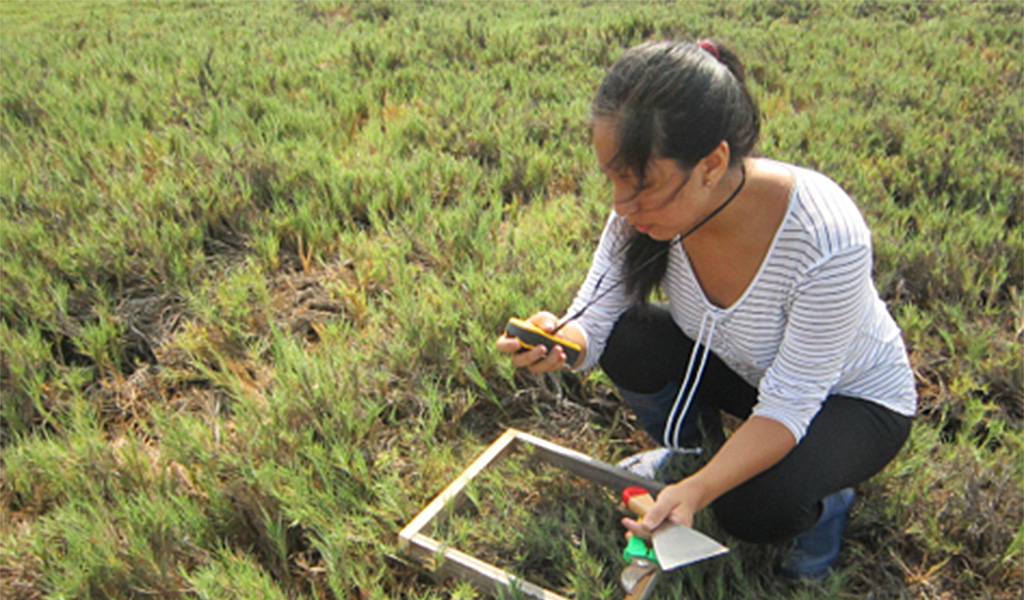

Karol Salazar Navarro, 25 years old from Lima, Peru, is a young scientist researching this topic, more specifically, how much carbon is taken up from the atmosphere and stored by a native grass species of the wetland. She’s concerned that people start to see both the beauty and value of this wetland’s blue carbon.

“It is frustrating to see that the wetland has been reduced in area over the years,” says Karol. On one side the city is encroaching, a university is on the other border, it is crossed by a road and there are also private areas in its surroundings such as country clubs and recreation fields.

Her own love of the wetland started as she began at university. “Every day I passed by the wetland ‘Pantanos de Villa’ travelling to university. I discovered the landscape from this route. During the day I could observe the birds and on the way home I saw the moon reflecting in the lagoon,” she says.

On of the way to get around the wetland is by boat.

Her own love of the wetland started as she began at university. “Every day I passed by the wetland ‘Pantanos de Villa’ travelling to university. I discovered the landscape from this route. During the day I could observe the birds and on the way home I saw the moon reflecting in the lagoon,” she says.

The wetlands, composed of marshes and swamps, with both fresh and saltwater lagoons across 263,270 hectares, is home to more than 200 species of migratory and resident birds including the Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Guanay cormorant and Peruvian Booby. It’s also a refuge for species like Peregrine Falcon and the Black-bellied Plover.

The discovery of this wetland’s charm, even from the periphery, led her to develop her thesis about the area.

“I grew up with a close connection to nature and water since I lived very close to the beach. From a very young age, I was convinced that I wanted to study something related to the environment and science. I am fascinated by the marine-coastal systems’ capacity to capture carbon.”

Striated heron, also known as mangrove heron is one the species that can be found in this wetland.

But as a young adult, science was distant to her: she imagined it was a career for others. “My image of scientists was of people in white coats who did not seem very accessible, she says.”

At the time in Peru, there were not many opportunities in public universities to study the environment. Fortunately, the National Technological University of South Lima, a new University in Peru, was offering a program for the first time in environmental engineering. With preparation and dedication, Karol entered the program, became part of one of the first cohorts and finished successfully in 2019.

“Part of safeguarding the wetlands is raising awareness of ‘blue carbon’. People need to know the important role wetlands play in carbon storage.”

Luckily, SERNANP and PROHVILLA, two institutions with whom Karol collaborated through her project, are working on preventing the wetland from begin used as a dumping ground. “Part of safeguarding the wetlands is raising awareness of ‘blue carbon’. People need to know the important role wetlands play in carbon storage. This is why I also work on identifying the existence and feasibility of methods for determining carbon sequestration, the capturing and storing of atmospheric carbon dioxide, in wetlands.”

One of Karol’s major successes has been finding a factor for estimating how much carbon is taken up from the atmosphere and stored in the species she studied. She compared three different methods to see if they gave the same results regarding the percentage of carbon sequestration. Using different methods she surprisingly found different results for each method, with results varying between 57.94 tons of carbon per hectare to up to 181.8 tons of carbon per hectare.

“I initially identified it as an error but managed to recognise it as a motivation to continue researching it. I hope my story will motivate more young people to study science. By doing this we can help restore and safeguard wetlands and their carbon stores.”