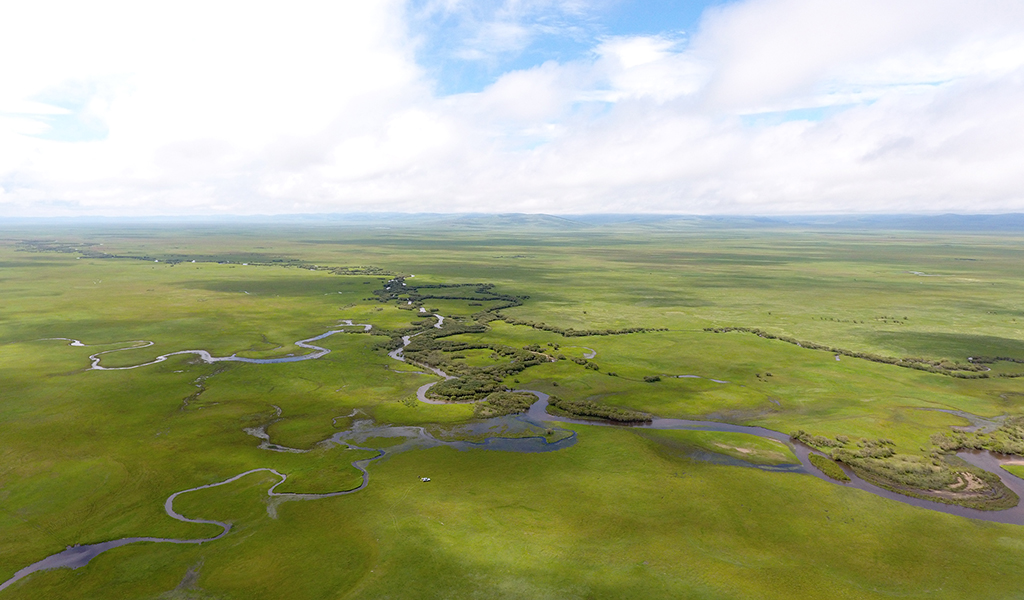

Every spring when the snow starts to melt on the Mongolian steppe, thousands of migratory birds land on the wetlands of the Khurkh and Khuiten river valleys in north-eastern Mongolia. Dubbed “crane capital”, the area is home to the threatened White-naped crane, the Demoiselle and the Common crane while the Siberian and Hooded cranes are also observed.

“We want to maintain its crucial property of storing carbon in its peat and methane in its permafrost.”

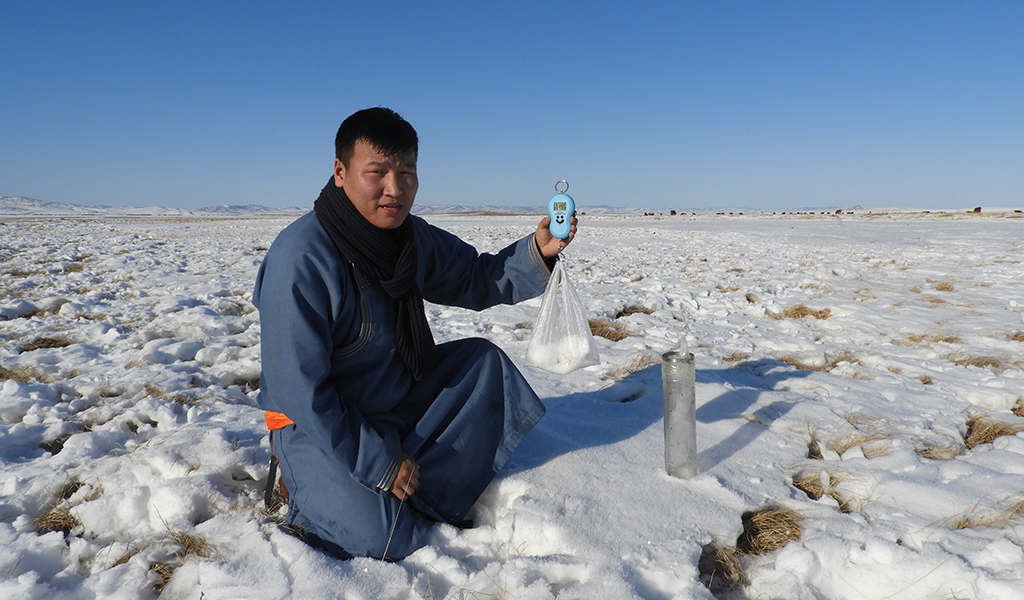

Wetland ecologist Vandandorj Sumiya, who works at the Wildlife Science and Conservation Center of Mongolia (WSCC ) and Research Fellow at the Leiden Conservation Foundation (LCF), has been managing a research project here to understand the climatic and anthropogenic impacts on the valley, and how to safeguard it for both the cranes, and the people who depend on it. He says: “we want to maintain its crucial property of storing carbon in its peat and methane in its permafrost.” Spring is when he prepares his field study with colleagues.

Vandandorj grew up in a herding family in the central Mongolian countryside, where he spent his childhood outdoors all day. “I used to try to pet chicks, fish, toads and bring them home. I would care for them, but my parents always asked me to let them go. This is when my interest in nature started and led me to studying and conserving wildlife in their natural habitat,” he says.

Khurkh and Zuunbayan Rivers.

“Mongolia has a big responsibility for the conservation of the crane species, having the highest density of breeding pairs in the valleys, but there will be no success without paying attention to its habitat, the wetland.”

The valleys Vandandorj works in are relatively small in size, but are internationally known for their cranes and as a carbon store, and because of this, have been designated a Ramsar site, an East Asia-Australasian Flyway Network site and Important Bird Area. More recently, the valleys were named a state nature reserve by Mongolian Government thanks to the efforts of international and national institutions, including WSCC.

Vandandorj explains that components of the wetland are fundamentally interconnected and interdependent. The peat layer of partially decayed plant material on top of the permafrost acts as insultation and prevents the permafrost from thawing. In turn, the permafrost holds the water table higher in the wetland, allowing the peat to stay in good condition. But, due to overgrazing and global warming Mongolia has already lost half its peatland habitats and the valley could face similar consequences.

White-naped Crane (Photo by WSCC/Iderbat Damba).

Overgrazing, mostly by domestic livestock, exposes the soil leading to higher surface temperature and an increased evaporation rate. This disturbs the interconnectedness between the peat layer and the permafrost, with the possibility of degradation of the wetlands, setting off a negative feedback loop. Vandandorj and his team is working to prevent this from happening and that the area would become unsuitable for nesting cranes.

He frequently travels to the valleys during the year for his studies and conservation activities, even in cold snowy winters. “Our field study is not as easy as people might think. Since it is a wetland sometimes you may have to walk about 30 km a day. When you go by car you can get stuck in the mud easily. But we enjoy our field studies a lot because we truly love this place and I believe that we are doing something meaningful for our nature, for the cranes and people as well,” he says.

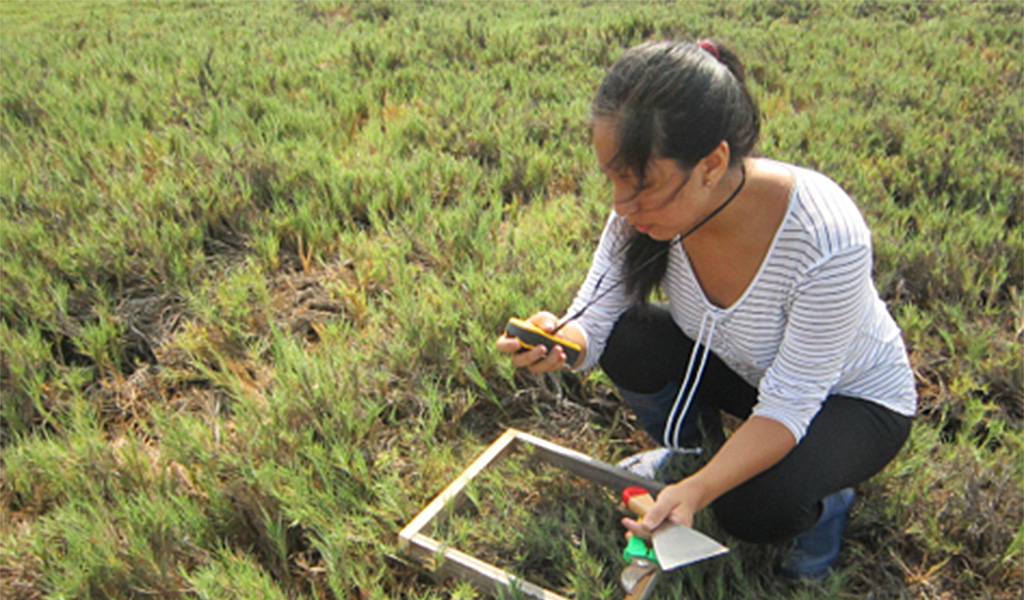

Apart from his academic studies, Vandandorj also organises annual training on wetland studies for young Mongolian researchers and runs an interactive summer school for local students, to help them to grow up as a nature-loving and responsible citizen. Students learn about the special birds that live in their region, how important the wetland is for the birds and local communities, and how they can help with conservation of biodiversity and the wetland.

Field practice of the capacity building training for Mongolian young scientists.

WSCC also works with herding community and provides training to diversify their source of income, so that grazing pressure in wetlands could be reduced. “Herders are starting to realise that it is hard to have a large number of livestock in the changing world and are more open to alternative livelihoods. Working with communities in wetland monitoring and wildlife conservation is important for the future of the wetland, its migratory birds and the people that depend on it,” says Vandandorj.