Stories about restoring and safeguarding wetlands are frequently about people acting on their conservation dreams of fighting for local biodiversity. They’re also often about friendship and a shared love of nature.

Alejandro Buitrago (28), Juan Borges (35), and Pilar Gómez-Ruiz (36) are three young wetland scientists and friends who have been working together to restore mangroves in the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve – a biodiversity-rich mangrove haven in Tabasco, southeastern Mexico, under threat from mining, logging and agriculture.

Covering 302,906 hectares, the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve comprises mangroves, freshwater wetlands, coastal dunes, aquatic and underwater vegetation. It is part of the largest wetland area in North America, home to species including red, black and white mangroves, howler monkeys, manatees, ocelots and alligators, as well as agami heron, the white pelican and the jabirú stork, Mexico’s largest bird.

Mangroves are essential for the communities around the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve.

But, like so many mangrove areas, this unique ecosystem is facing threats from industrial activities including mining, logging, agriculture, overfishing and urbanisation. Climate change is also a threat because of the increased impacts of forest fires. These fires can have a severe impact, resulting in a loss of mangrove cover and causing underground fires that are very difficult to control, Paulo says.

Pilar and Paulo met first when they were doing their PhD and Master, respectively, at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México, placed in Morelia city in 2012. Then, Alejandro met Paulo working together during a consultation project for the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) in the city of Villahermosa in 2017. The group teamed up to design a project in 2019 that would restore mangroves, increase community resilience and enhance the ability to adapt to climate change.

“These are actions that promote conservation and management of ecosystems and resources considering the benefits that they provide to human societies and biodiversity. We worked with two communities in the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve to develop more understanding about the value of their wetland and how to make use of its resources in a sustainable way,” says Alejandro.

Due to the close cooperation with the local communities, the project has strengthened people’s idea about the importance of conserving and restoring their mangroves.

The trio secured funds through the Resiliencia project (a GEF fund powered by UNDP and the Mexican Governement) on behalf of Foro para el Desarrollo Sustentable NGO. Before the project started, the team did a more in-depth study of the local livelihoods and threats and defined a way to manage the mangroves and decrease vulnerability to climate change.

“It is essential to involve young people in mangrove monitoring techniques since they will be the future managers of restoration projects in their communities.”

Mangroves are essential for the communities around the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve. They act as a nursery for species like shrimps, crabs and other freshwater fishes. Naturally, fishing is a major livelihood. Pilar adds: “Mangroves are also important to protect communities against tropical storms and strong winds, it helps reduce flooding impacts.”

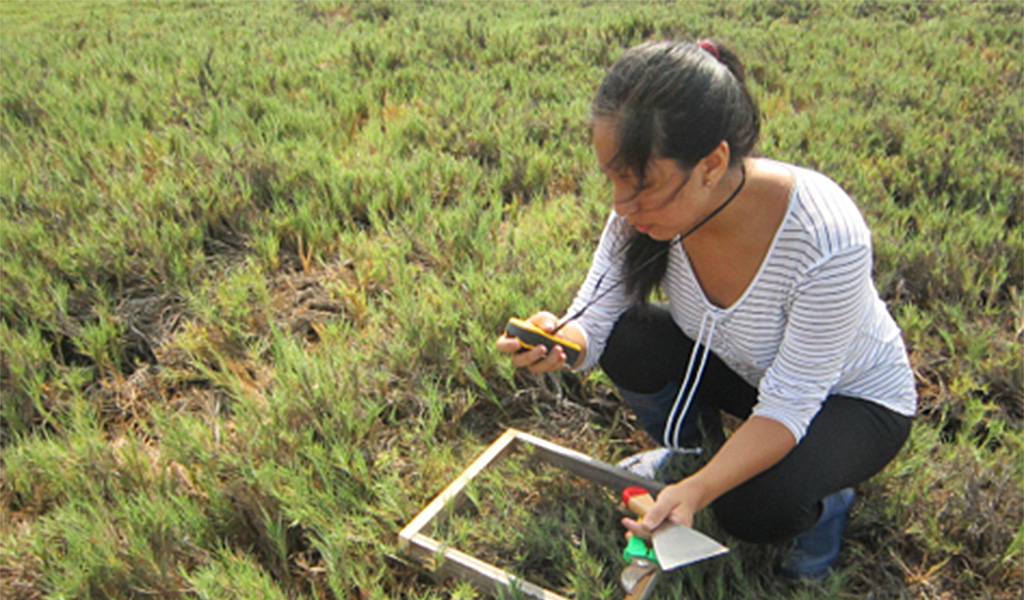

The project brought science into practical terms for communities, and locals have actively participated in workshops and restoration work. Pilar says: “As mangrove restoration is a very long process, it is important that the communities take ownership of the process and its monitoring. Due to the close cooperation with the local communities, the project has strengthened people’s idea about the importance of conserving and restoring their mangroves. This is important since they are the people who will benefit from a healthy system the most.”

Being taken seriously as a young project manager has been a challenge for the trio, according to Paulo. “As young people, it is a challenge to build projects and manage resources through bids. But we were lucky with the team, because we all have experience with this. Although at first, we felt that some people did not take us very seriously, especially the managers of the natural area and the people who gave us the financing, after listening to our ideas and proposals, people recognized that we are very capable.”

As a young female researcher, Pilar also faced significant challenges. “Sometimes young people do not have enough credibility in spaces traditionally dominated by older people, a situation much more evident in rural areas because knowledge is associated with age. As a woman, I noticed a difference when I led some activities in the community where I could perceive some resistance and mistrust at the beginning. As the project progressed, people had more trust in me,” she says.

For Pilar, wetlands are extra special as they have unique conditions that only certain species can tolerate.

Before this project, women and youth had very few opportunities to be involved in decision-making processes as this is traditionally done by men in the communities. The trio made extra efforts to ensure women and youth participated. “In this sense, the project was very rewarding to me. It is essential to involve young people in mangrove monitoring techniques since they will be the future managers of restoration projects in their communities,” says Pilar.

The project has now run for over a year but the last activities took place in February 2020 due to the COVID pandemic. The group will be sharing results with the local people later this year. The next step will be to strengthen sustainable fisheries to improve local livelihoods together with the communities, as well as to keep monitoring the restoration.

“We are exploring post-COVID and post-disaster recovery work, because the communities were very affected by floods during the second semester of 2020. We will work on improving food and water security by constructing agroecological orchards and water reservoirs, building firebreaks to protect mangroves and doing maintenance and monitoring of mangrove restoration process,” says Alejandro.

“I was fascinated by the idea that these ecosystems produced the freshwater for all citizens. This fascination lead me to where I am now.”

So what was it that drew them to wetlands in the first place? For Pilar, wetlands are extra special as they have unique conditions that only certain species can tolerate. “Studying them gives a great opportunity to do cool research,” she says.

Alejandro’s love of wetlands started with his childhood hikes through the paramos and other wetlands that surrounded Bogota city. “I was fascinated by the idea that these ecosystems produced the freshwater for all citizens. This fascination lead me to where I am now,” he says.

Paulo also spent his childhood in wetlands. Growing up in Merida, 30km from the sea, these were coastal. “I spent my childhood holidays at the coast. I was amazed by the big trees that grew in the water, and where beautiful birds’ nests were built. I did not understand why people said these wetlands were just breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Many years later, when I did my studies, I learned more about the fascinating adaptations and great importance of mangroves not only for the species living there but also to the people who live there and benefit from this ecosystem. This provoked in me a deep reflection on the urgent need to conserve and restore this ecosystem.”