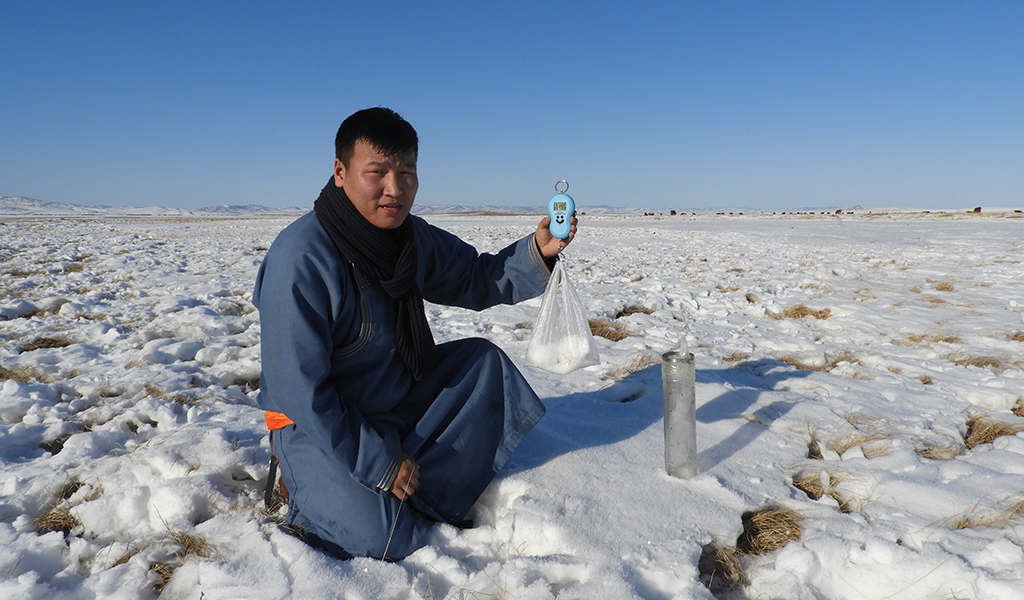

Wetlands high up in mountains are often remote and harsh places, blasted by wind and rain, with all seasons possible in a day. But while their social sparsity might suggest a lack of importance, they are in fact, fundamental to thousands of cities around the world; as a vital source of freshwater, fed by melting snow and glaciers.

“They are natural ‘water towers’ because of their ability to collect water and release it slowly through time.”

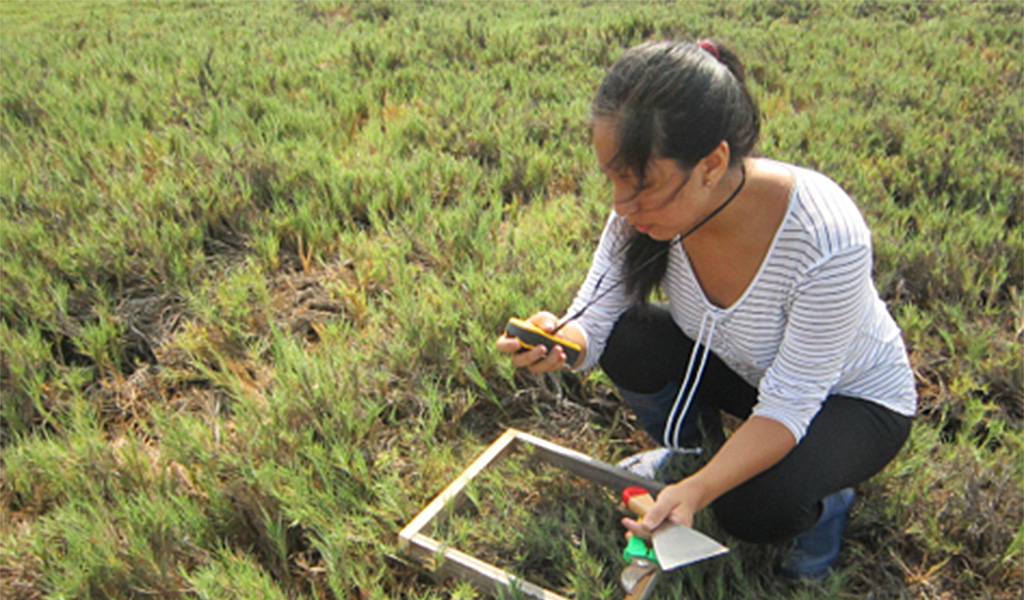

Thirty-three year old Ecuadorian, Maria Sánchez, is someone who recognises just how crucial to life these wetlands are. Born in the second highest capital city in the world, Quito, Maria has been studying how mountain peatlands are affected by a shift in winter precipitation due to climate change for the past two years. “They are natural ‘water towers’ because of their ability to collect water and release it slowly through time but they are disproportionately affected by climate change,” she says.

One of Maria’s favourite sites is the Helen Lake peatland in Banff National Park in Canada. “It is super hard to hike in all the equipment there, because we are not allowed to leave it in. But the views are amazing and it is so peaceful and quiet. I feel very grateful I get to work there.”

One of Maria’s favourite sites in the Helen Lake peatland in Banff National Park in Canada.

To survive in these conditions, life has to be hardy. Mountain peatlands are also the home of very specific species that have adapted to live in what are often harsh conditions. These ecosystems may see all the seasons in one day, and these adapted species thrive there, says Maria.

Among these, the Alpine Bearberry’s shortness allows it to stay alive through high winds, avalanches. It protects itself from cold by staying under the snow. Sphagnum moss, meanwhile, acts like sponge to hold huge amounts of water and allows peat to accumulate.

What fascinates María most, however, is the way that organic matter has managed to still gather over landscapes that have changed so much — through landslides, volcanic eruptions, and glacier retreat. “It is also awe-inspiring how these peatlands have accumulated carbon for over ten thousand years in such small places. Peatlands in the mountains are not vast and flat, they are small but very prevalent,” she says.

The Alpine Bearberry (Arctostaphylos alpine) is a shrub adapted to high elevation. Its shortness allows it to stay alive through the extreme climactic conditions of the region.

Unfortunately, high-altitude wetlands are rapidly being degraded due to the drainage of mountain peatlands, conversion of lakes and channelisation of rivers. The loss of upstream wetlands threatens the health and safety of billions of people downstream by reducing the capacity of the landscape to store water. This prevents the replenishment of groundwater and increases the risk of water scarcity and flash floods.

“Studying mountain peatlands is an essential step for conservation as these ecosystems are an essential piece of the hydrological cycle. María says: “It is incredibly important that we turn to look at them now: to inventory them, characterise them, and include them in our studies, because we may end up losing entire ecosystems, without knowing they existed or how they worked.”

Maria’s path, from her environmental engineering degree to her passion for mountain wetlands, was not always easy. “I somehow felt I was missing something. I later understood that a great component of my satisfaction with work was to be outdoors in the field understanding ecosystems by observing them,” she says.