Across the world millions of people and animals depend on healthy wetlands. The riverine Marura wetlands, running across western Kenya, is no exception.

“Many people are not aware of the power of wetlands and how their lives are linked to the health state of it. This is what we hope to change.”

Long associated with the cyperus papyrus, the paper reed, originating from the Sergoit River, the Marura wetlands span an area now characterised by agriculture, block making, harvesting, fishing, livestock rearing and irrigation. Locals derive more than 50% of their livelihood from the wetland’s resources. The wetlands are also home to migratory birds including crowned cranes, water ducks, great egrets, and marsh wrens.

But, the wetlands are under coming under increasing threat as settlements of both commercial houses and homes have grown significantly along the bank. These bring more pollution and the tendency towards over-harvesting of fish, water, and papyrus.

Using these precious wetlands in ways that help sustain the wetlands is key to avoiding loss and is something that 25-year old Leonard Agan, from Eldoret, a main fast-growing town in Kenya’s Rift Valley region, is activating his community around.

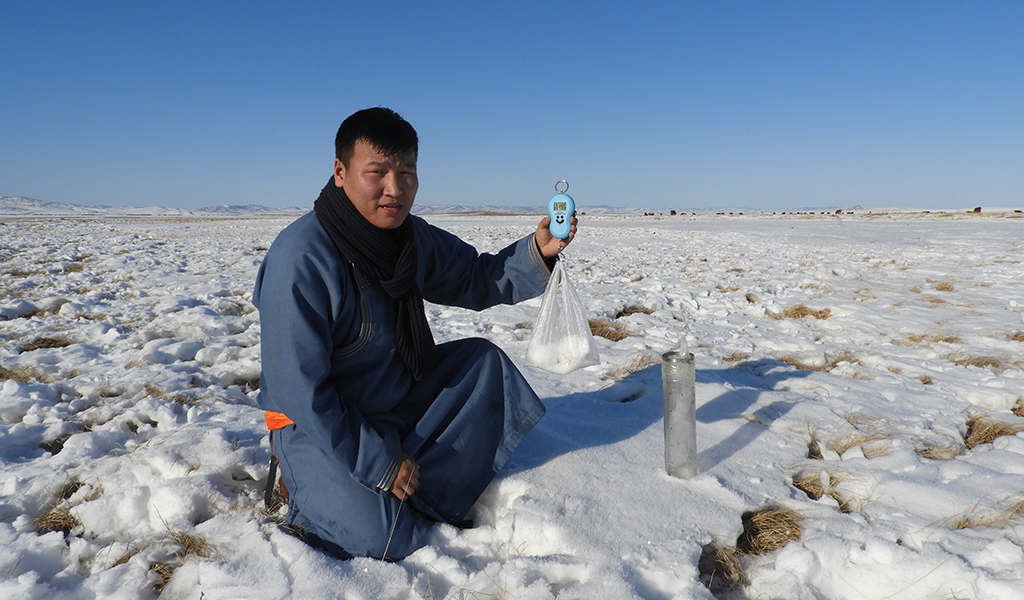

Chepkoilel river

After visiting the Marurar wetlands a number of years ago, and having studied a master’s in Environmental health at the University of Eldoret, Leonard got to understand the vital role and services that the wetlands provide. “Like the provision of water, fish and herbs, or the indirect services like the potential to control floods from upstream,” he adds. Leonard wants to make sure these services will be secured for the long-term.

Leonard is developing a group of like-minded young people who want to raise such awareness among the local people. This group has been engaging the local community, schools and farmers on the important roles wetlands play in their lives and livelihoods.

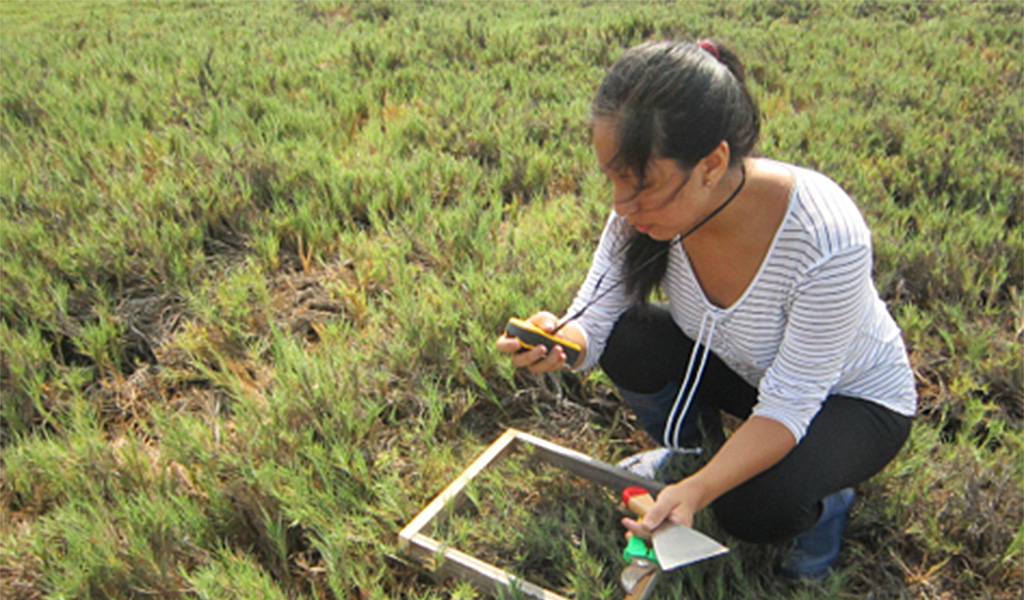

Team instructions in the field

“We aim to make conservation and sustainable development a culture and attitude of people.”

Changing ingrained practices will be part of the challenge. Currently, people tend to cut a whole reed area down. This influences groundwater storage, and the fish and other aquatic organisms end up exposed to direct sunlight.

“We hope to inform and inspire people to get the products from the wetland in a way that it can be continuous without total destruction. Many people are not aware of the power of wetlands and how their lives are linked to the health state of it. This is what we hope to change,” says Leonard.

While getting access to schools or different parts of the community can sometimes be a challenge, the group has been translating information materials English to Kiswahili to reach more people with the message. “By engaging with them we hope to reduce waste in the wetlands and to stop over-exploitation, we aim to make conservation and sustainable development a culture and attitude of people,” he says.