As natural buffers against storms and floods, nursing grounds for fisheries, sources of wood for fuel and timber, and hotspots of biodiversity, mangroves are a vital lifeline for people and nature. But, mangroves are being lost rapidly as cities, agriculture and aquaculture expand. And, being in remote locations, means that it’s even more difficult to pinpoint the causes.

“It’s hard to believe that wetlands are often still viewed by humans as useless land.”

One young wetland ambassador working to change this is Alexander Watson, based in Krefeld, Germany. With his heart and soul in landscape recovery, this ‘nature-inspired’ entrepreneur specialises in supporting civil society organisations and communities with the remote sensing, data analysis, visualisation and map-based communication tools needed to safeguard or restore their forest landscapes, including mangroves.

“Mangroves make landscapes and ecosystems more resilient. As border ecosystems between land and water, they have a structural diversity and provide a habitat for many rare plant and animal species. It’s hard to believe that wetlands are often still viewed by humans as useless land,” says Alexander.

Mangrove protecting the cost land, El Salvador

Alexander graduated as a forestry scientist but without any formal wetland training. It was during a hike in Panama in 2008 that began in the rainforests when he came to realise just how vital water is by connecting our ecosystems and he had an idea for how to help people value these ecosystems.

Alexander during a hike in the Panamanian cloud forests.

“The air had over 90% humidity. Everything was slightly wet. The surfaces and mosses on the trees were soaked with water. The forest floor was muddy and repeatedly crossed by small streams. Mud had formed on flat surfaces into which you sank deep beyond your ankles,” he says.“The hike followed the water, along small streams down to the sea on the Caribbean side. There was no white beach there, but mangroves. This hike, in which I followed the water, from the fog of the mountains to the sea, showed me how water connects ecosystems,” he adds.

He realised that by monitoring these landscapes closely via satellite imagery and by making their visual diversity accessible via high-resolution aerial images, he could help people value these ecosystems. It’s only what we see, understand, and connect with that we are going to protect, he says.

Following this vision, Alexander and two friends started OpenForests in 2011, and today the team has grown to 12 people supporting more than 150 projects around the world.

The hiking journey downhill to the mangroves

However, it took some time for Alexander and his co-founders to find their way. It started with making aerial photographs by mounting a normal camera to a helium balloon. Unsurprisingly, operating a balloon on a rope in a windy forest presented some challenges.

Mounting a camera with a balloon.

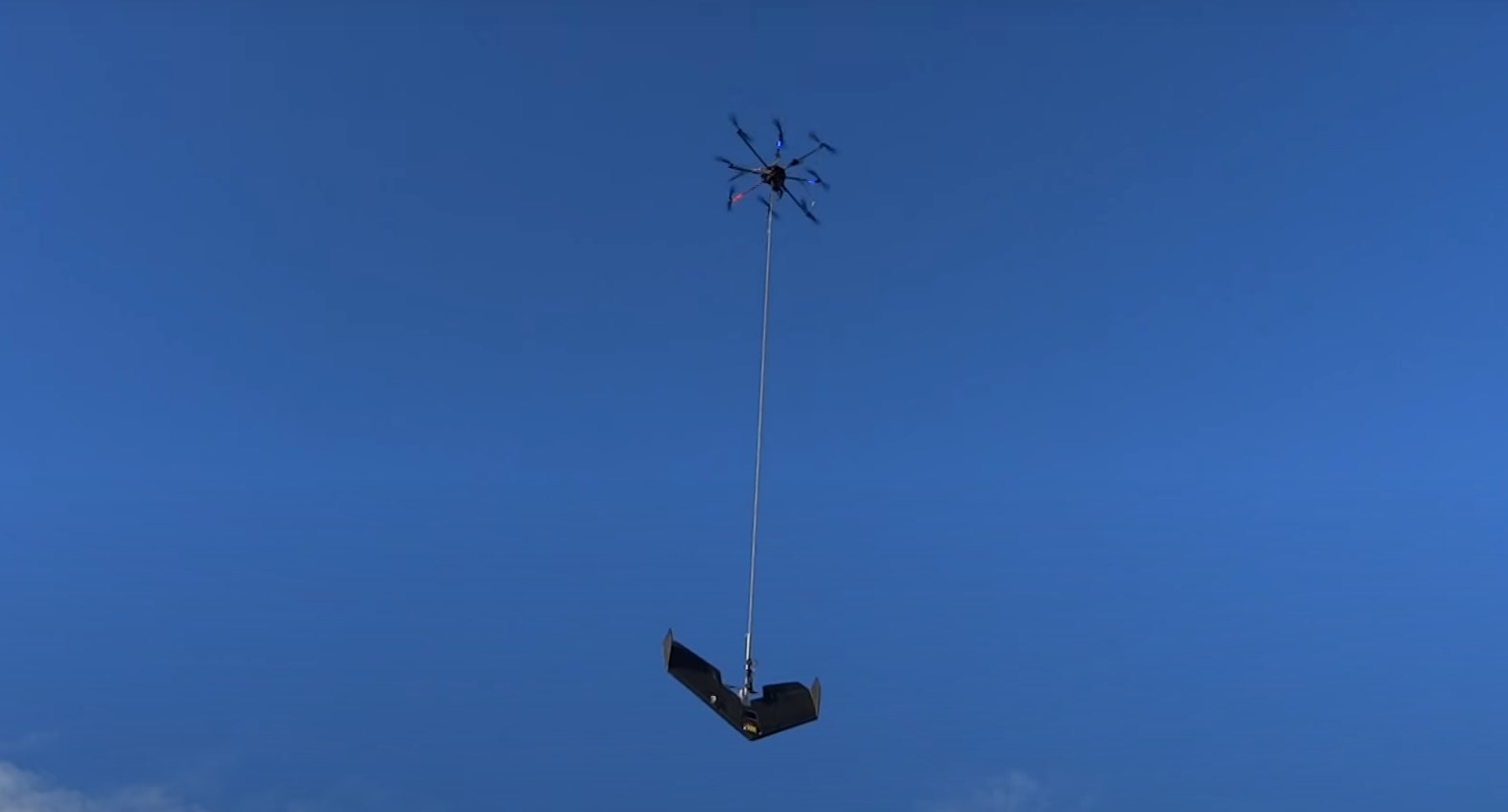

Experimenting with the first available drones, which came out shortly after, helped the team improve and they mapped up to 100 hectares a day, producing high-quality images. This led to their first consultancy contract. Armed with a brand new drone necessary for the job, and bought with €10.000 scraped together from friends, the team set out to Suriname.

But, day one, flight one, in front of all clients, the prized drone crashed into a tree and was badly damaged. It took the team three weeks to carry out repairs, only to run into repeated problems with take-off in a dense forest. To avoid yet another crash, they decided to haul the drone above the canopy, using a helicopter drone and a rope, thus securing a safe take-off – for the drone and the business.

Mounting the fixed-wing glider drone with a copter drone 2015 Suriname.